A MICROSCOPIC LOOK AT THE SONORASAURUS SITE, COCHISE CO., ARIZONA

Richard Hill

Lunar & Planetary Lab., Univ. of AZ

Ron Ratkevich

Paleontologist, Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum

This paper was given at the Fossils of Arizona Conference, Nov., 1996

and published in the proceedings of that conference, available from

the Mesa Southwest Museum in Mesa, Arizona.

ABSTRACT

This is a report on the microscopic examination of samples on

loan from the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum (ASDM) of the

Cretaceous (Albian-Cenomanian), Turney Ranch Formation,

"Sonorasaurus" site. The site, in the Whetstone Mountains,

Cochise Co., Arizona, is currently being excavated under the

direction of the ASDM. A lack of microfossils in the coarse

sandstone matrix led to an examination of bone chips contained in

the loaned samples. Thin sections of these bone fragments were

made and compared to other such sections from known dinosauria in

an attempt to determine if bone histology could aid in the

taxonomic classification of "Sonorasaurus."

INTRODUCTION

Thayer & Ratkevich (1995) have detailed the work being done on,

and the then current state of analysis of the "Sonorsaurus"

(field designation) in the middle Cretaceous, Albian-Cenomanian

age, Turney Ranch Formation being excavated near the Whetstone

Mountains, Cochise Co., Arizona. Shortly after the Fossils of

Arizona Symposium, 1995, it was proposed by Ratkevich that a

search for microfossils be conducted in the matrix of this site

to verify the age.

The Turney Ranch Formation beds at this site are composed of

coarse to fine grained sandstone. It has been described in detail

in several publications. Tyrrell (1957); Titley (1968); Thayer

(1995).

Material was received by Hill from Ratkevich and the ASDM on 22

April, 1996. The loaned samples consisted of 6 pieces and some

small fragments that had broken off in transit, with a total

weight of 6.7 kg. They were mostly matrix with some bone

fragments included (largely periosteum that adhered to the

matrix).

PART I

PROCEDURE

Work was begun immediately using techniques outlined in Jones

(1956). Three samples of approximately equal weight (400-500 g)

were broken up. Two were immediately disaggregated. One sample

was treated with a weak solution (approx. 3%) of muriatic acid.

It was soaked for one hour, then thoroughly washed and sieved.

The other was boiled for several hours (in a microwave oven) with

a high molecular weight soap (Quaternary-O), thoroughly washed

and sieved. Both produced very similar results. The third sample

was, at a later date, soaked in a room temperature solution of a

different high molecular weight soap, Eldorado Amine Q-O, for

about two weeks. It was washed like the former samples.

Two of the samples, the two soaked in soap solutions, were

weighted by sifted grades. The results can be seen in Table 1.

Though the samples selected were only of approximate weight prior

to reduction, they were within 3 grams afterwards. No attempt was

made to capture soil smaller than 0.11 mm (110 microns). This

becomes important later.

=================================================================

TABLE 1

_________________________________________________________________

Screen Avg. Weight % Comments

Grade Size (grams) of

(mm) Total

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Sample 1 -

#5 >5.1 44.75 23.2 Mostly conglomerations

of grains with tiny bone

chips

#5-10 3.4 12.76 6.6 Some conglomeration of

grains and tiny bone

chips

#10-35 1.1 42.08 21.8 fully reduced grains

#35-60 0.54 72.65 37.7 " "

#60-120 0.28 16.06 8.3 " "

#120-230 0.14 4.39 2.3

Sample 2 -

#5 >5.1 44.00 23.1 Mostly conglomerations

of grains with tiny bone

chips

#5-10 3.4 12.41 6.5 Some conglomeration of

grains and tiny bone

chips

#10-35 1.1 41.33 21.7 fully reduced grains

#35-60 0.54 72.90 38.3 " "

#60-120 0.28 15.71 8.3 " "

#120-230 0.14 4.04 2.1

=================================================================

RESULTS

What is immediately obvious from the table is that the median

particle size is about half a millimeter, with over half of each

sample (by weight) between 0.4-2.5 mm.

Polarization showed the composition of the sandstone was largely

quartz and feldspar with an admixture of a number of other

elements that were not individually determined.

To date, this careful reduction and picking through about 600

grams of raw rock has produced little and no unambiguous

microfossil fauna. The most interesting find is a small coprolite

consisting of tiny bone fragments.

Suggestions were made that palynology be done with this material.

Present laboratory conditions do not permit the use of the acids

necessary for such reduction nor are there means readily

available for the retrieval of sediments below an average

particle size of 140 microns.

PART II

As the search for microfossils continued to yield little,

attention turned to the encased bone fragments. Preliminary

classification of "Sonorasaurus" was based on fragmentary,

unprepared skeletal elements. An initial determination that the

specimen represented a sauropod (Ratkevich 1994) became suspect

when E.H.Colbert suggested hadrosaur affinity (Colbert 1995) and

later, a possible relationship to therizinosaurs was presented

verbally by D.W.Thayer at this Symposium in 1995. Thayer's

determination was based on what appeared at first to be a large

manus claw, since determined to be a chevron. This was the only

time "Sonorasaurus" was considered a carnosaur. Examination of

the remains by several paleontologists, including elements not

available a year ago, have again suggested that "Sonorasaurus" is

a sauropod. However, to date no teeth have been recovered for

this dinosaur adding to taxonomic uncertanties. It was hoped a

comparative microscopic study of bone specimens from this and

some other dinosauria could help shed some light on the taxonomy

of "Sonorasaurus".

There were two fossilized bone tissues found in the loaned matrix

samples. These consisted of the periosteum of several larger

bones that adhered to the rock when large bones were removed and

several centimeter sized and smaller pieces of dense bone. There

is little doubt that the bone is indeed from "Sonorasaurus". Some

of the pieces were that which had apparently remained from

excavation of the long bones of "Sonorasaurus". Slices were made

of the dense bone and thin sections were made using methods

described in Allman & Lawrence (1972). Though only small amounts

of the bone were available, the quality was very good. Fragments

of other identified (albeit often poorly) dinosaur bone were

obtained for comparisons and thin sections made in similar

manner. In all over two dozen thin sections were made.

Terminology and descriptions of bone elements have been described

elsewhere, Reid(1966), Fastovsky & Weishampel(1966), and will not

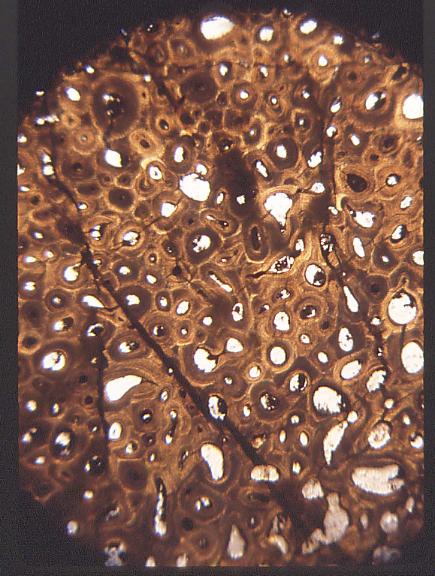

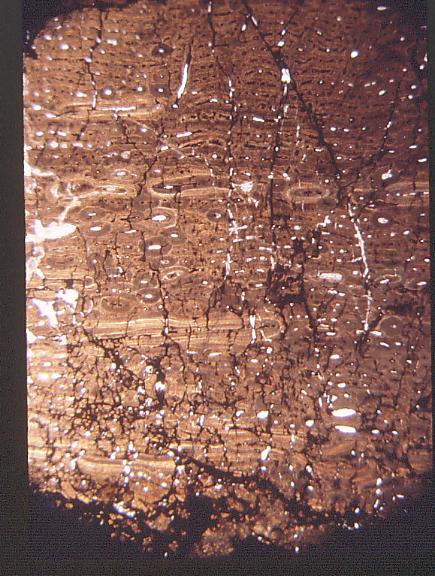

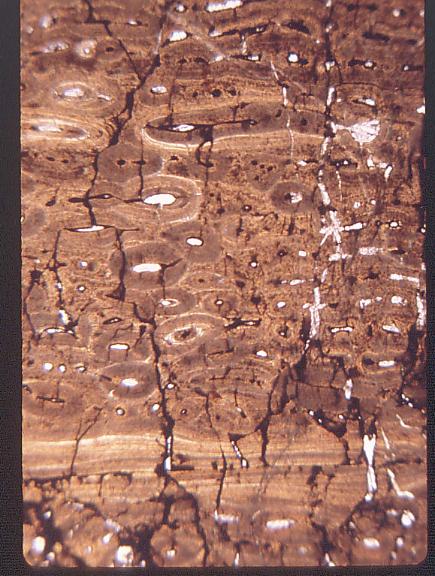

be again defined here. Examination of the thin sections showed

that all samples of "Sonorasaurus" displayed Haversian Systems

and in several thin sections, reconstruction to cancellous bone

could also be seen. No unambiguous periosteum was found in

contact with the dense bone fragments and in most cases dense

bone was found in direct contact with the matrix. Thin sections

of the comparison bones (Allosaur, Apatosaur, several

indeterminate Jurassic sauropods, an indeterminate Hadrosaur and

a Ceratopsian) displayed a wide variety of bone types. Only those

that showed Haversian systems or dense bone are presented as

comparisons here.

There were two methods used in evaluating the thin sections, the

qualitative and quantitative. Morphologically there was only one

specimen that had an appearance similar to "Sonorasaurus" bone,

the thin section labeled sp1. This was an indeterminate sauropod

from the Morrison Formation of Colorado. Not satisfied with a

simple visual comparison Hill measured the minor axis of 20

randomly picked secondary osteons in most of the slides and

obtained the results shown in Table 2. Of the three best samples

of Apatosaur, Hadrosaur and the indeterminate Sauropod from the

Morrison Formation, the latter showed the closest size

correlation to secondary osteons of "Sonorasaurus". There was a

slight statistical sampling difference in that four

"Sonorasaurus" sections were sampled while only one Apatosaur,

one of the indeterminate Sauropod, and two of the ideterminate

Hadrosaur were sampled. This was not felt to be significant when

these results were taken in consideration with the qualitative

morphological examination.

TABLE 2

Measurements of secondary osteons

________________________________________________________________

Bone Sample # Mean +/- Comments

----------------------------------------------------------------

"Sonorasaurus" sn1 0.35 0.08

" sn2b 0.28 0.07

" sn4a 0.29 0.09

" sn3b 0.31 0.11

Mean 0.31 0.08

Apatosaur ap1 0.24 0.06

indeterminate Sauropod sp1 0.29 0.06

sp4 0.27 0.05

Allosaur al1 0.38 0.11 not Haversian?

Hadrosaur hd1 0.35 0.09

hd3 0.37 0.18

Ceratopsian ct3 0.31 0.08 not Haversian?

ct4 0.33 0.05 "

----------------------------------------------------------------

These results are, in a word, inconclusive. The closest match was

the indeterminate Sauropod long bone from the Morrison Formation

but that is not without qualifications: 1) the bone is of a time

period well before the Albian, 2) we do not absolutely know from

what type of bone the "Sonorasaurus" sample came though it

appears to be bits remaining from long bones extracted from the

same rocks, and 3) there is a possible bias in the respective

qualities of preservation of all the different samples used.

This experiment was conducted on a personal budget with those

samples that could be readily acquired. It would be highly

desirable for this experiment to be repeated using the following

constraints and guidelines:

1.) All samples be either rib, long bone, or vertebrals, but not

a mix, from identified adults.

2.) All samples come from the middle of the Cretaceous,

specifically the Albian/Cenomenanian if possible.

3.) Five types be sampled: brachiosaur, titanosaur, hadrosaur,

iguanodont, and nodosaur.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The following persons graciously donated samples for this work:

Alan & Carol Prandi, and Japheth B. Boyce.

The first author wishes to thank the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum

for including him in this exciting project.

References:

Allman, Michael, and Lawrence, David F., (1972) Geological

Laboratory Techniques, ARCO Pub. Co., Inc, New York

Colbert, E.H., (1995) Personal communication to Ratkevich

Fastovsky, David E., and Weishampel, David B., (1996) The

Evolution and Extinction of the Dinosaurs, Cambridge Univ. Press,

N.Y.

Jones, Daniel J., (1956) Introduction to Microfossils, Harper &

Brothers, p.7-18.

Ratkevich, R., see Thayer, D.W. (1995)

Reid, R.E.H., (1996) "Bone Histology of the Cleveland-Lloyd

Dinosaurs and of Dinosaurs in General, Part I: Introduction:

Introduction to Bone Tissues", Brigham Young Univ. Geological

Studies, Vol.41.

Sattler, Hellen Roney, (1983) Dinosaur Dictionary, Lothrop, Lee &

Shepard Books, New York.

Thayer, D.W., Ratkevich, R.P., (1995) "In-Progress Dinosaur

Excavation in the Mid-Cretaceous Turney Ranch Formation,

Southeastern Arizona.", Fossils of Arizona - Vol. III,

Proceedings 1995, Southwest Paleontological Society and Mesa

Southwest Museum, Mesa, AZ.

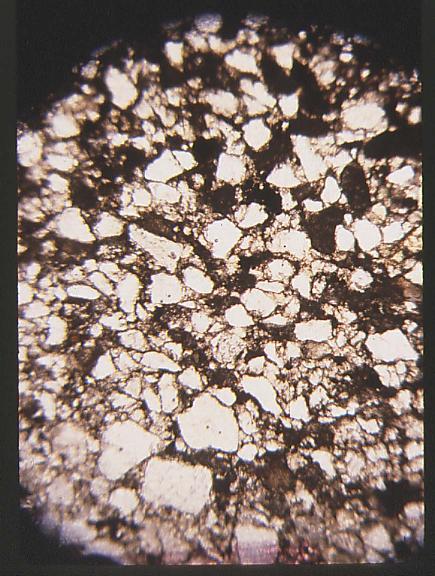

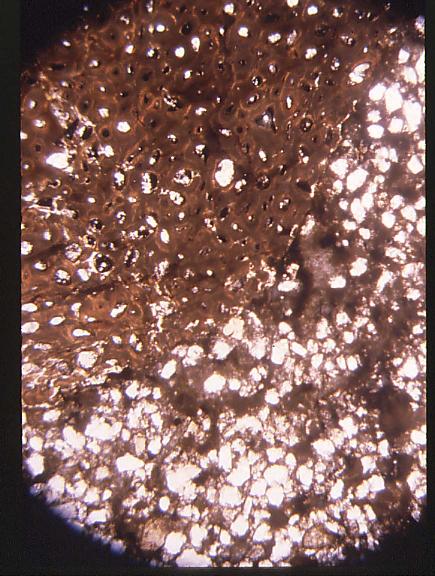

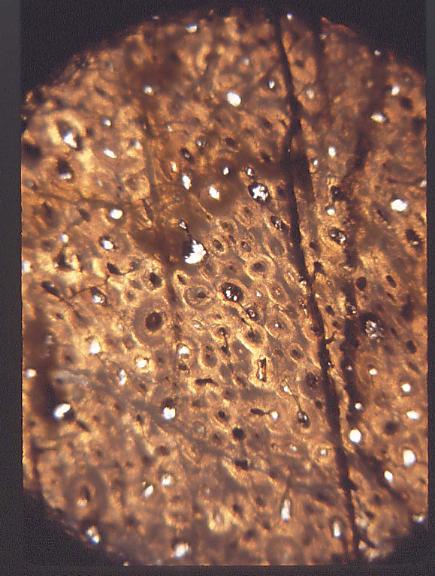

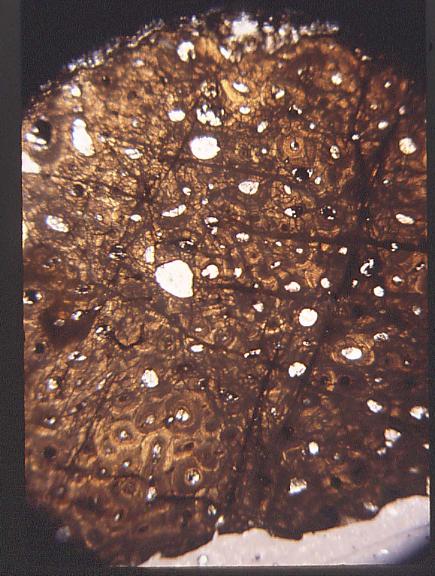

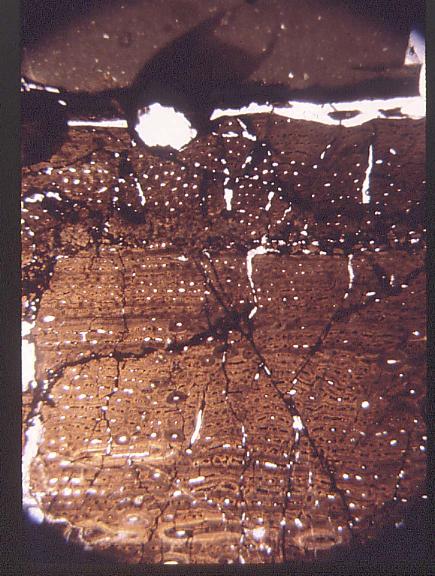

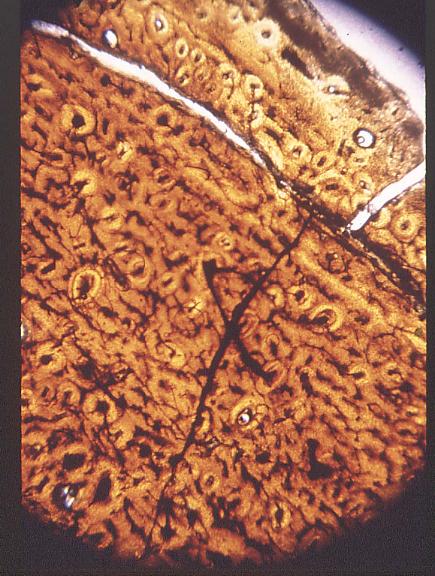

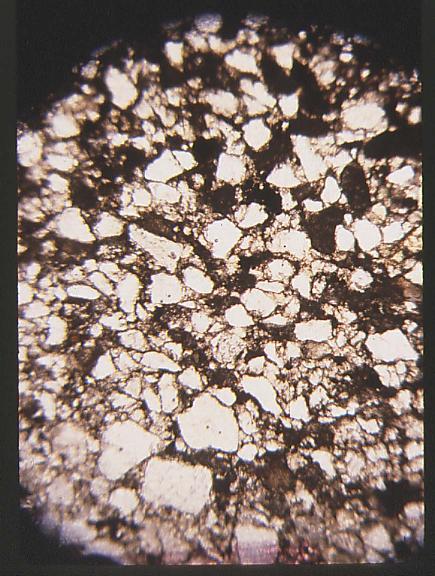

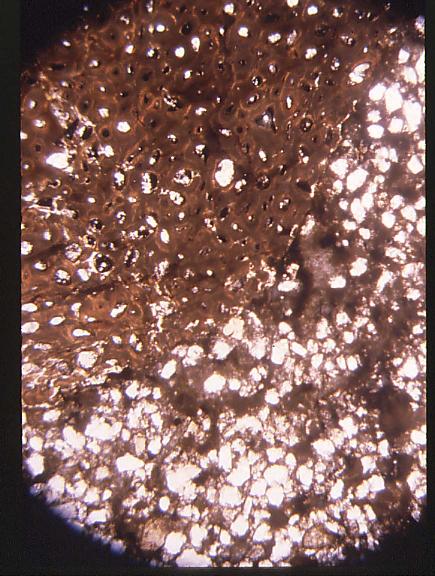

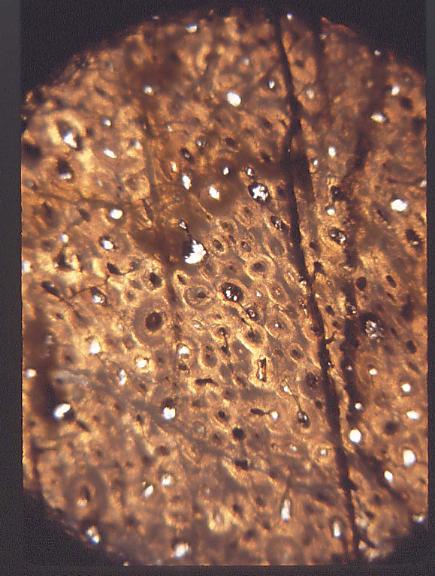

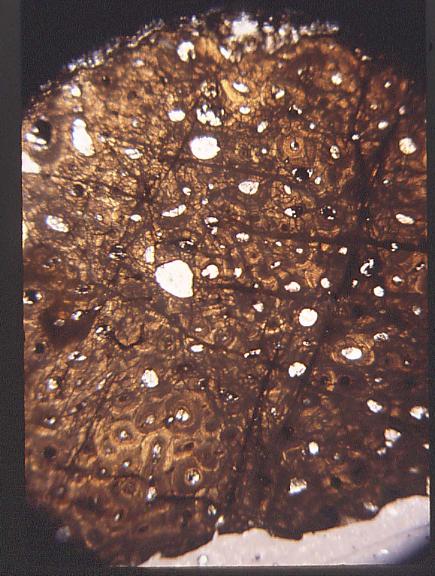

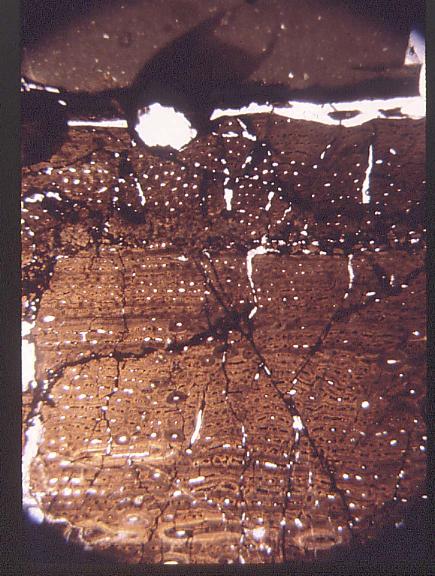

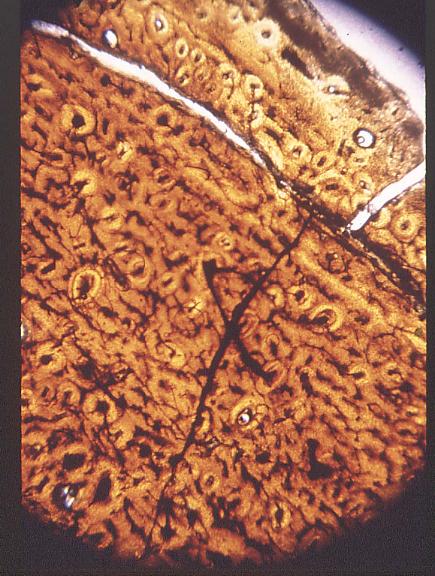

fig.1 Slide sn1 - Matrix showing the structure of the Turney Ranch

Formation at the "Sonorasaurus" site. 20x

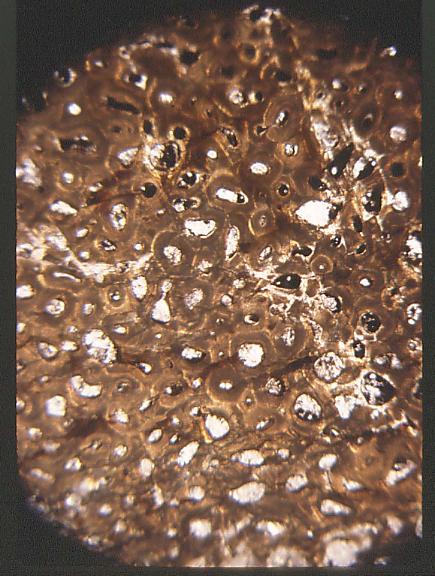

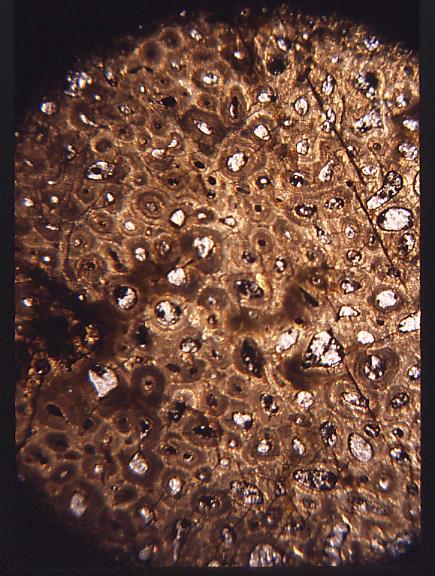

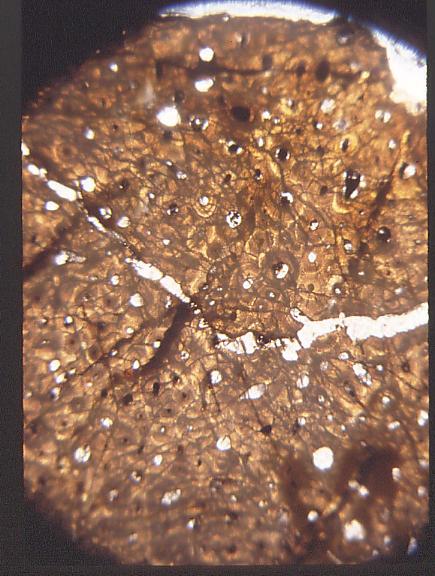

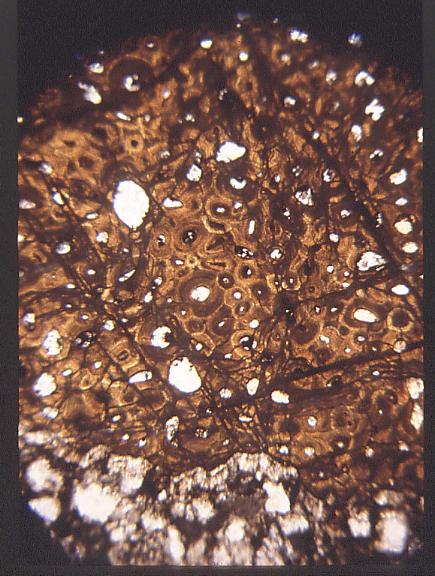

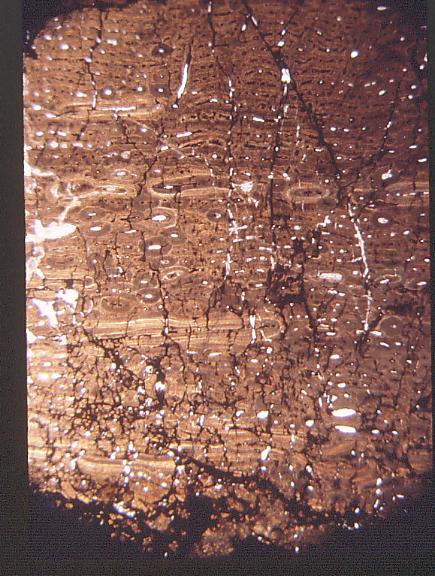

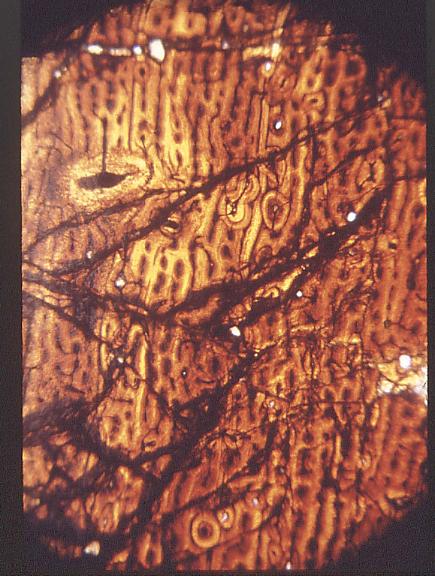

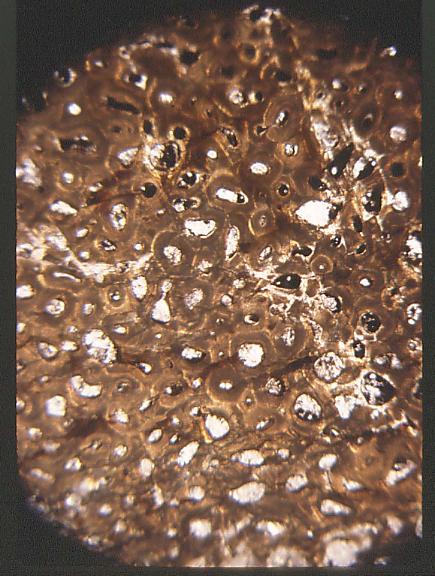

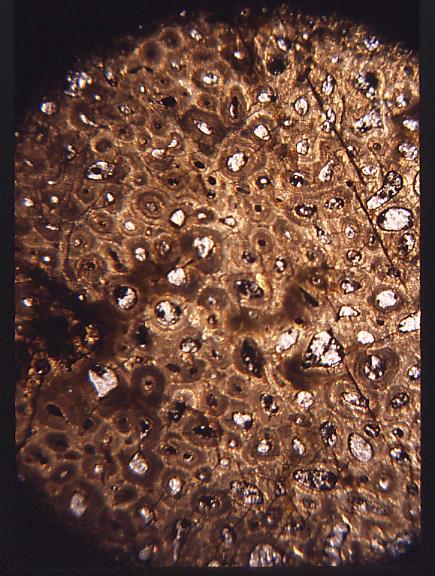

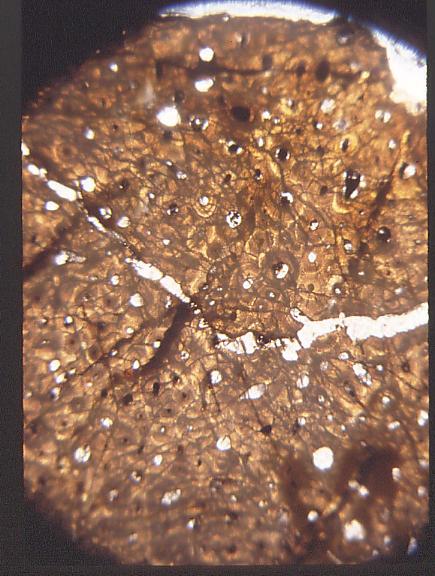

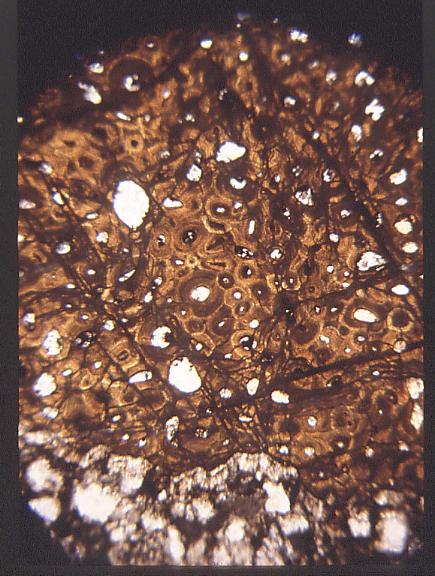

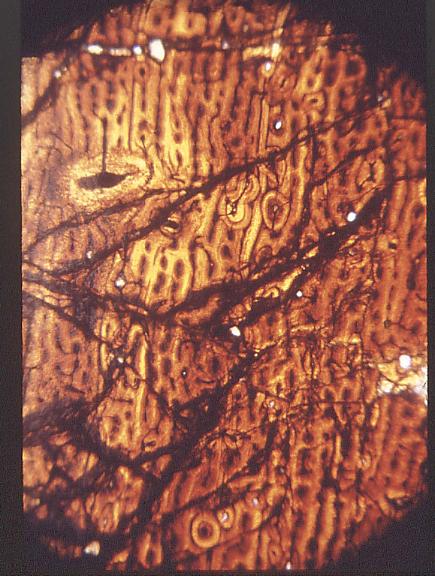

fig.2 Slide sn1a - "Sonorsaurus" secondary cancellous bone

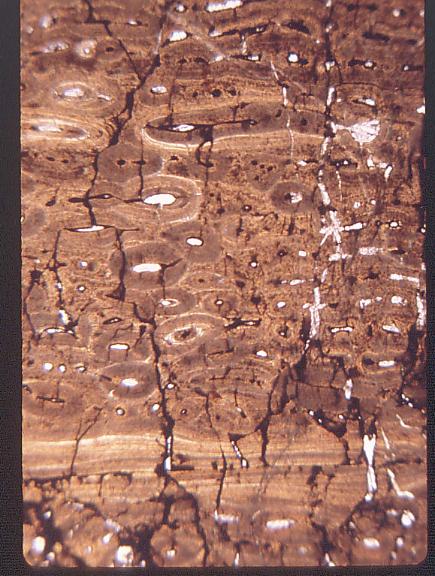

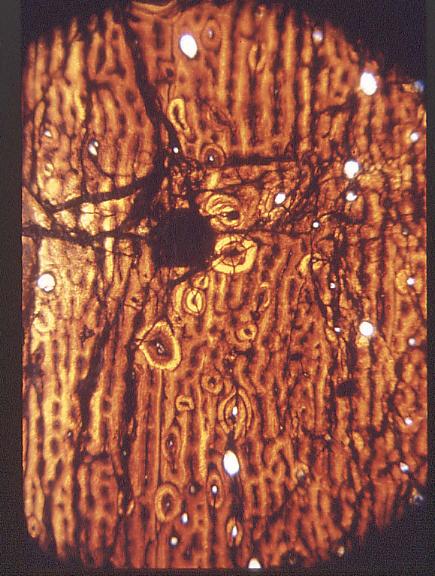

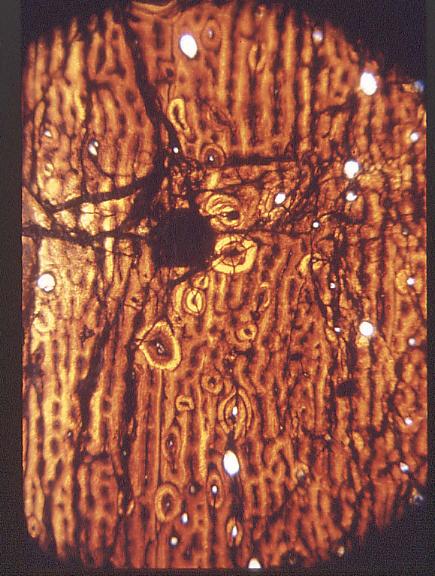

replacing Haversian bone. 20x

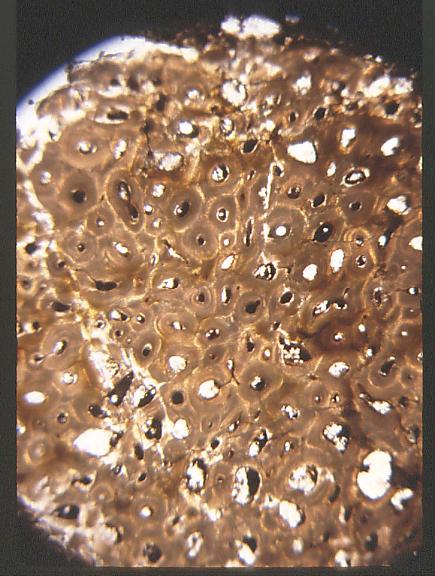

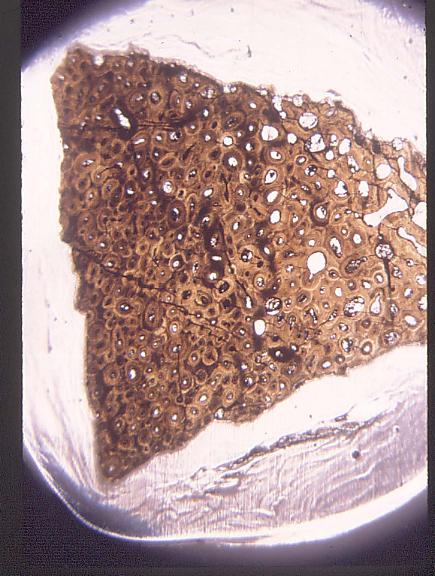

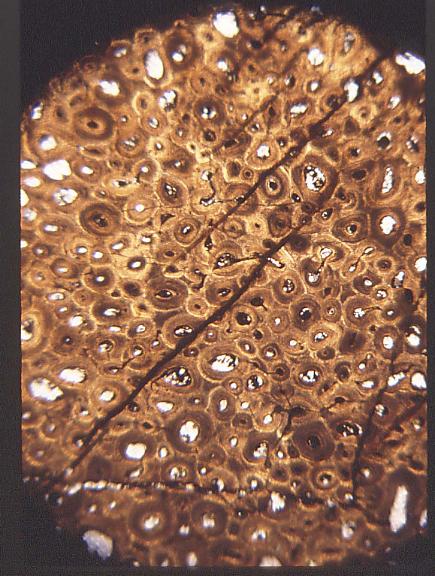

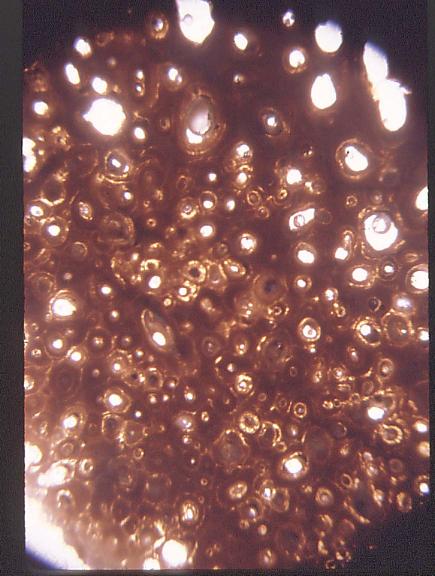

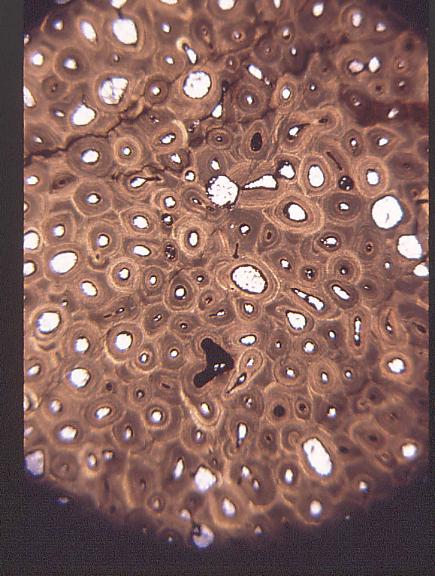

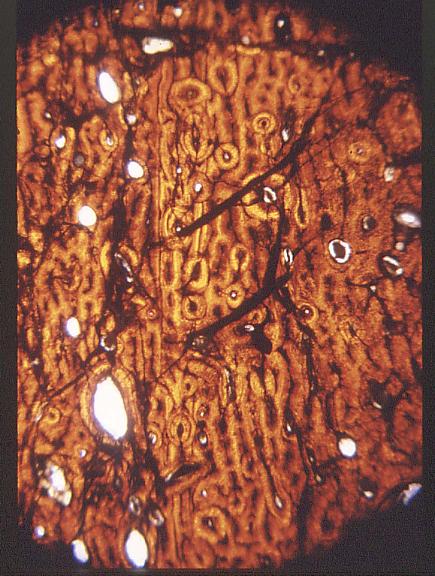

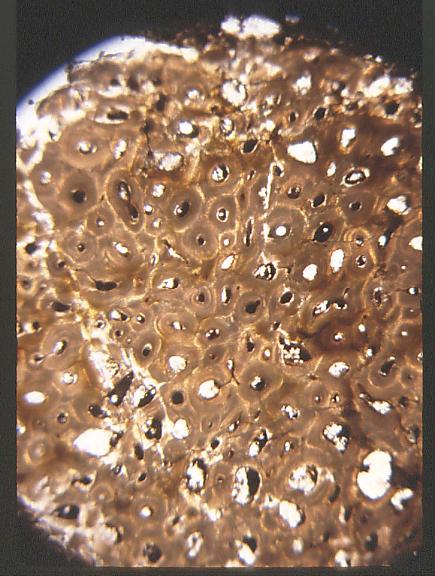

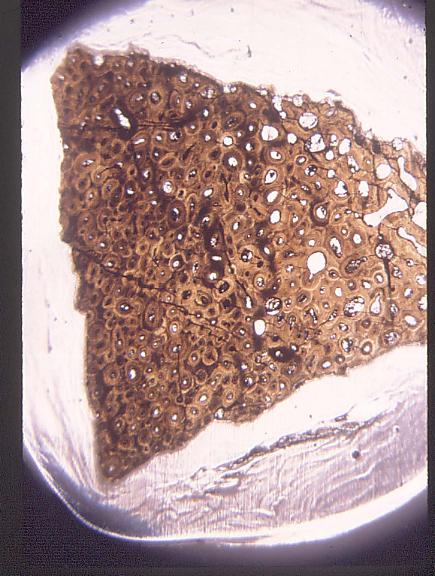

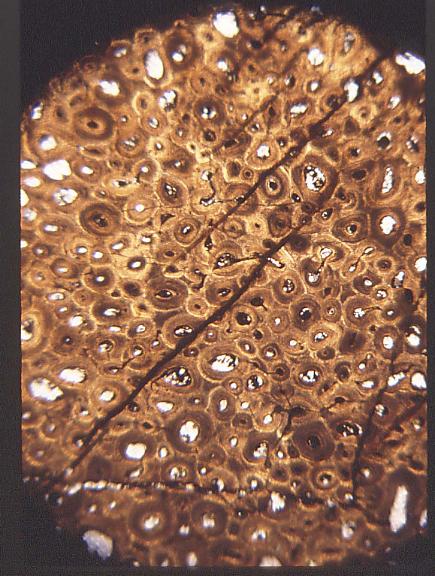

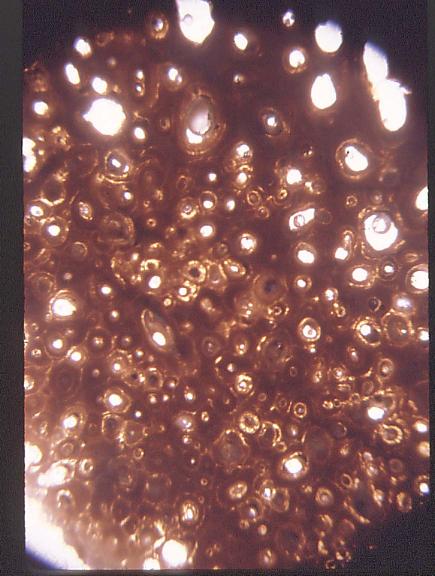

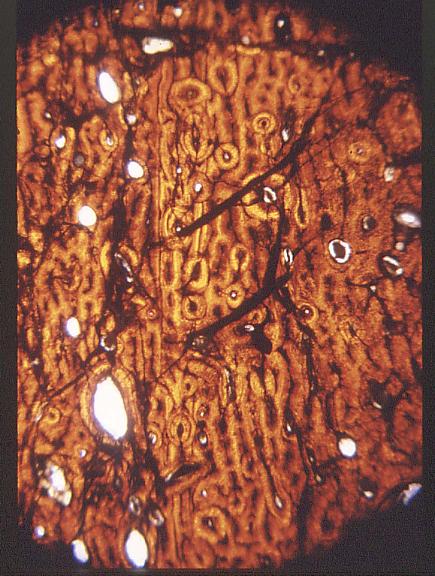

fig.3 Slide sn1b - Region adjacent to sn1a showing mostly compact Haversian bone with some cancellous bone replacement. 20x

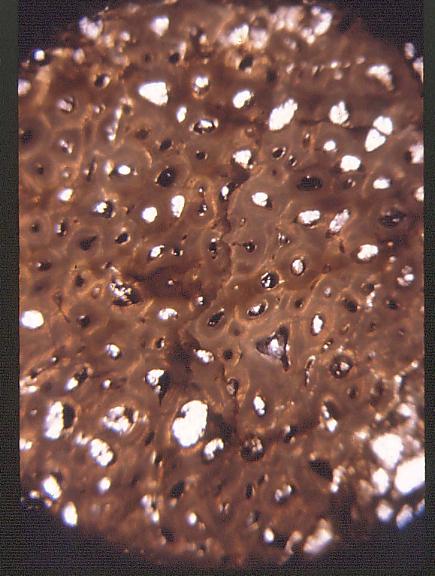

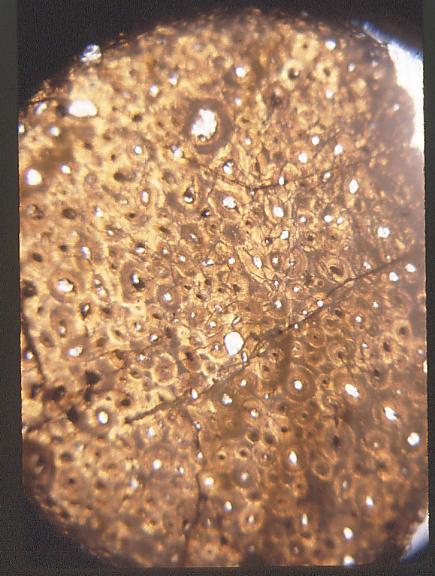

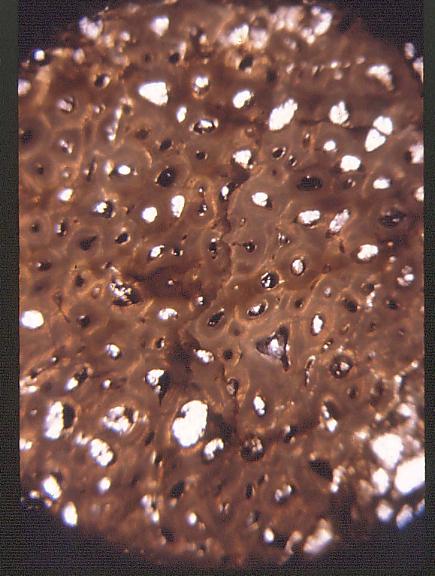

fig.4 Slide sn1c - Region adjacent to sn1b showing mostly dense Haversian systems. 20x

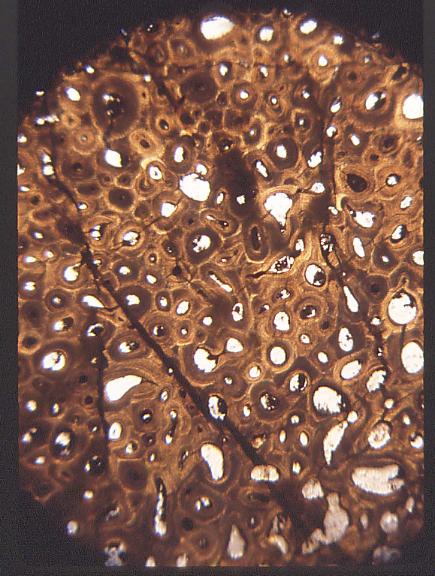

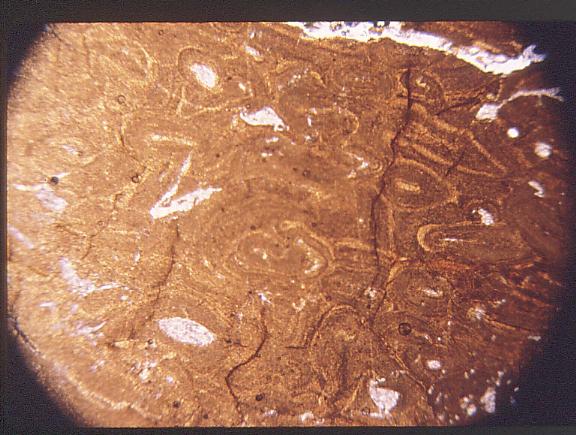

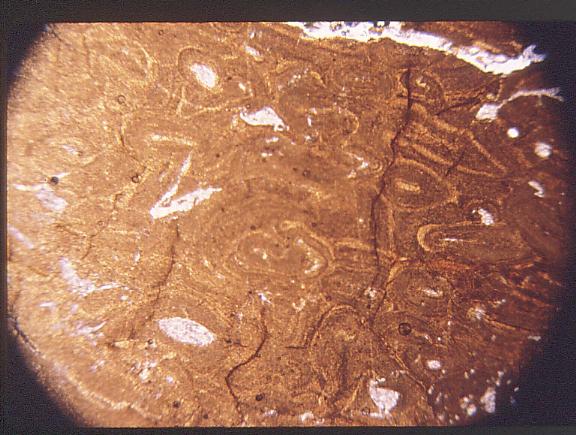

fig.5 Slide sn1d - Region including much of and adjacent to sn1c, the contact of compact Haversian bone with the matrix. Note the lack of periosteum with dense bone in direct contact with the matrix. 13.5x

fig.6 Slide sn2a - Haversian bone grading into cancellous replaced bone. 20x

fig.7 Slide sn2b-a - The whole bone piece about 5mm long showing compact Haversian bone and the base grading into cancellous bone at the apex. Note again the lack of periosteum on any perimeter. 13.5x

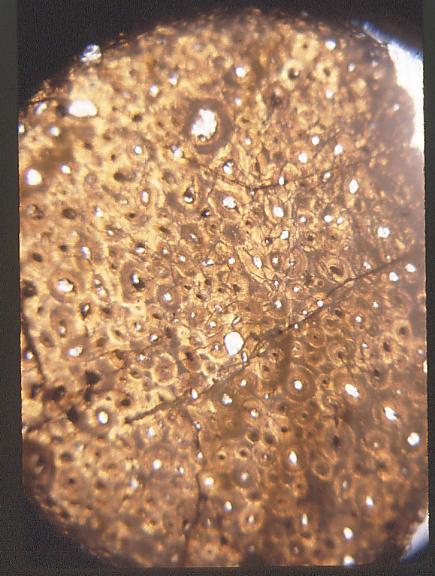

fig.8 Slide sn3a - Compact Haversian bone with some reconstruction. 20x

fig.9 Slide sn3b - More compact Haversian systems. 20x

fig.10 Slide sn3c - Mostly compact Haversian bone with possible primary osteons in one corner. 20x

fig.11 Slide sn4a - Compact Haversian bone with some reconstruction to cancellous. Note internal structure of secondary osteons. 20x

fig.12 Slide sn4b - Secondary cancellous bone replacement of Haversian bone. 20x

fig.13 Slide sn5a - Secondary cancellous bone replacement of Haversian systems. 20x

fig.14 Slide sn5b - Contact between compact Haversian bone with matrix. Note again, no periosteum. 20x

fig.15 Slide ct4 - Ceratopsian haversian systems surrounded by cancellous bone.These were the only secondary osteons seen in any of the Ceratopsian specimens. 20x

fig.16 Slide al1 - Allosaur, probably Compacted coarse cancellous bone. Most likely not long bone. 20x

fig.17 Slide ap1-a - Apatosaur long bone showing siltstone matrix in contact with periosteum followed by lamellated bone. Some secondary osteons enclosed in the lamellated bone. 13.5x

fig.18 Slide ap1-b - Apatosaur long bone as above but further toward center of bone, with more secondary osteons in lamellated bone. 13.5x

fig.19 Slide ap1-c Apatosaur long bone with a closer look at secondary osteons of ap1-b. 20x

fig.20 Slide sp1 indet. Sauropod haversian bone with some reconstruction to cancellous. 20x

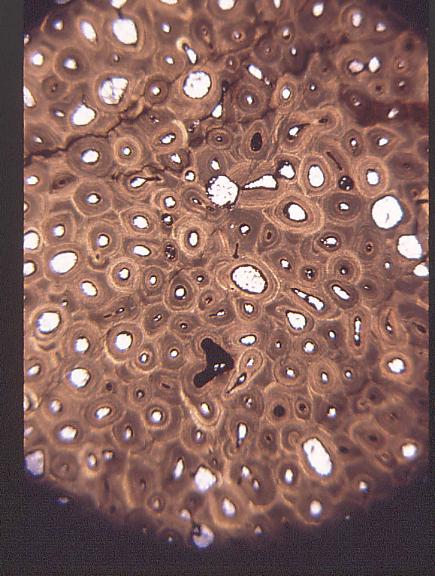

fig.21 Slide had1 - Long bone of ideterminate Hadrosaur from the Lance Creek Fm.

of Wyoming. Fibro lamellar bone with periosteum. 20x

fig.22 Slide had3-a - As fig.21 - some secondary osteons seen. 20x

fig.23 Slide had3-b - As fig.21 - with well defined secondary osteons. 20x

fig.24 Slide had3-c - As fig.21 - with secondary osteons and some reconstruction to cancellous bone. 20x

For questions contact:

rhill24@cox.net

---END---